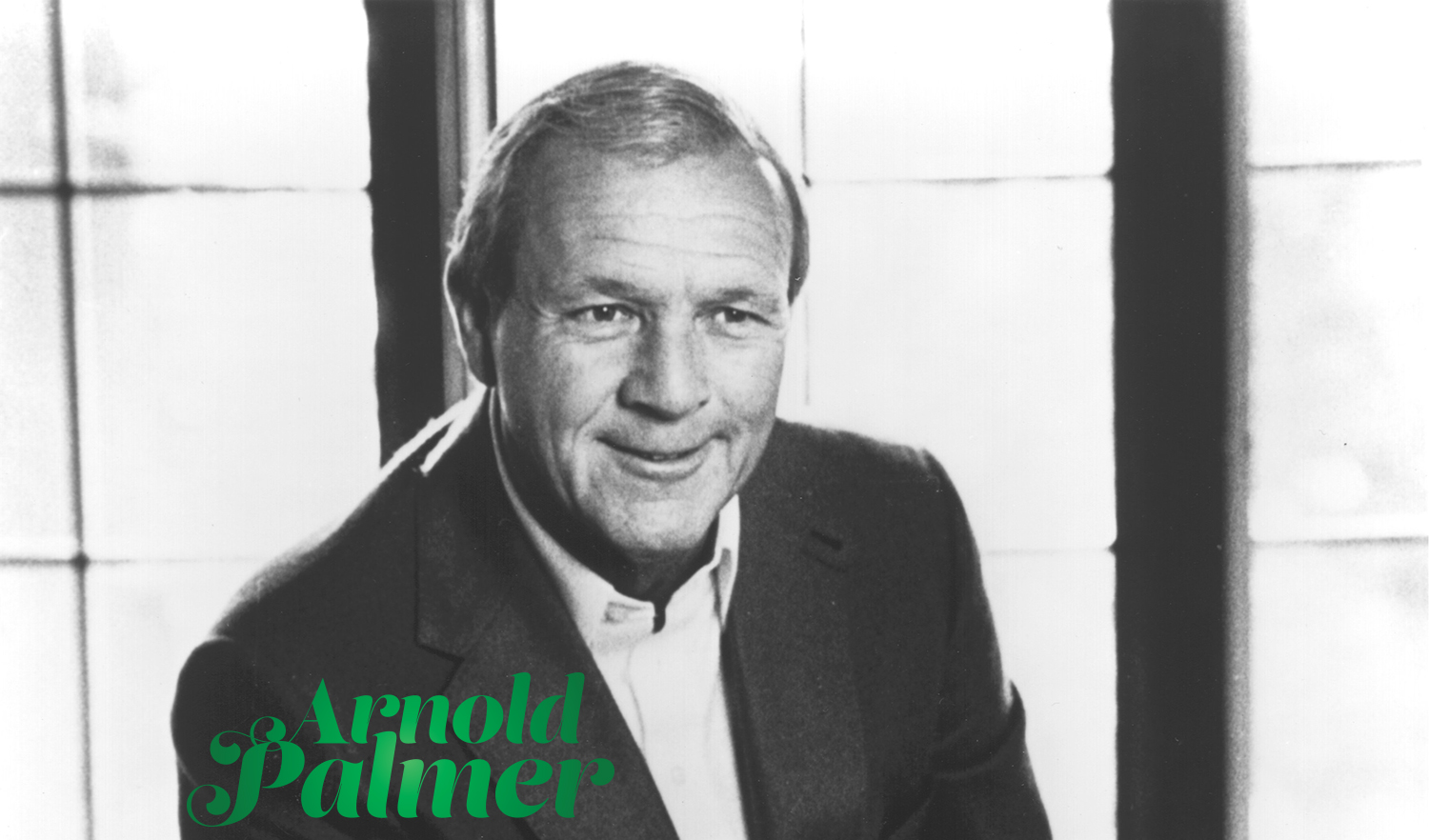

The late golfing legend and successful businessman never hesitated to publicly acknowledge that business aviation was a key to his success.

Oct. 31, 2016

There was no doubt about it: It was the worst of times. In 2008, the economy plunged into what would become known as the Great Recession, the most severe economic downturn since the Great Depression of the 1930s. While fingers of blame were pointed in many directions, business aviation became one of the most visible scapegoats, particularly after executives from the nation’s largest U.S. auto manufacturers traveled via company airplanes to Washington, DC, in September 2008 to ask the federal government for bailouts.

Fortunately, soon thereafter, a champion for business aviation stepped forward. Arnold Palmer, golf legend and accomplished businessman, said what few public figures at that time were willing to express – that using business aircraft “is the single most productive thing I have done. It’s given me the opportunity to compete more effectively in golf and in business, and it’s enabled me to do both from a place not served by the airlines.”

Palmer’s comments, featured in a so-called “truth advertisement” produced by NBAA, became one of the cornerstones of the No Plane No Gain campaign, the advocacy program jointly sponsored by NBAA and the General Aviation Manufacturers Association.

As a keynote speaker at NBAA’s 2009 Business Aviation Convention & Exhibition in Orlando, FL, Palmer explained why he felt compelled to lend his voice to the No Plane No Gain campaign. “I know the value of business airplanes. I know what they have done for me and my companies. I know how important they are to my hometown. And I know how important they are to this country. So I wanted to speak out and help set the record straight.”

We needed a leader to rally behind. Arnold Palmer was willing to use his stature and credibility to promote business aviation at a time when we needed it most.

Not long after taking the lead in advocating for the industry, Palmer’s decision to speak out for business aviation paved the way for other highly recognized and respected leaders – including Neil Armstrong and Warren Buffett – to join him as spokesmen for the No Plane No Gain. Soon, others joined the growing chorus of business aviation supporters.

“When the Arnold Palmer No Plane No Gain testimonials first became public, I had several people in the industry tell me that when they heard the negative press about business aviation, they began to feel bad about being part of the industry, but when Arnold came forward, it changed the way our industry viewed itself,” recalled NBAA President and CEO Ed Bolen. “We needed a leader to rally behind. Arnold Palmer was willing to use his stature and credibility to promote business aviation at a time when we needed it most.”

For more than five decades, Palmer relied on a variety of business airplanes, from pistons through jets, to support his work as a golf professional and his many successful business endeavors. In all, he owned or leased more than 10 aircraft, giving him a firsthand understanding of their value in optimizing efficiency and productivity.

Today, the No Plane No Gain campaign continues to educate policymakers and opinion leaders about the value of business aviation to citizens, companies and communities across the United States, thanks to the momentum created by having a well-respected person such as Arnold Palmer having spoken up during a time of crisis. Until the end of his days, Palmer continued to advocate for business aviation whenever federal legislators and regulators considered policies that could negatively affect the industry.

AVIATION ROOTS

Arnold Palmer always believed in business aviation, because the American icon had used it successfully for more than half a century, accumulating nearly 20,000 hours of flight time in the process.

Like many flyers, Palmer’s interest in aviation began at an early age. He made balsa wood airplanes as a boy growing up in Latrobe, PA. When he was 12 years old, a friend’s older brother took him up for what he recalled was a wild ride in a Piper Super Cub.

That experience, combined with an episode several years later during which he witnessed a ball of static electricity (St. Elmo’s Fire) roll down the aisle of a commercial DC-3 he was traveling on, might have dissuaded most people from becoming a pilot. But after Palmer became a touring golf professional in 1955, he soon realized how much easier it would be to fly between golf tournaments instead of driving long hours from town to town.

For more than five decades, Palmer relied on a variety of business airplanes, from pistons through jets, to support his work as a golf professional and his many successful business endeavors. In all, he owned or leased more than 10 aircraft, giving him a firsthand understanding of their value in optimizing efficiency and productivity.

Palmer decided that as soon as he could afford it, he would obtain his pilot’s license. Using some of the winnings from his early golf tournament victories, Palmer started taking flying lessons in 1956 at Latrobe’s local airport under the tutelage of Babe Krinock, a patient instructor who Palmer said was one of the best teachers he has ever flown with.

In short order Palmer began using general aviation to facilitate his golf career. After about two weeks of flight training he asked his instructor, “Babe, am I ready for a cross-country flight?”

“You were ready a week ago,” responded Krinock.

“I have an exhibition in Akron, OH. Can I take the airplane by myself?” Palmer asked.

“No problem,” answered Krinock.

BECOMING AN AIRCRAFT OWNER

After winning the 1958 Masters – the first of his seven major golf titles – Palmer leased a Cessna 175 and hired a part-time copilot to fly with him. In 1962, he bought his first airplane, a previously owned Aero Commander 500 piston twin. Two years later, he bought a brand-new Aero Commander 560F.

By the mid-1960s Palmer had stepped up to jets, and starting in 1976, he owned a series of Cessna Citations, which he used not only to facilitate a hall-of-fame professional golf career, but to parlay his success on the golf course into a series of successful business ventures. Over the years, these airplanes helped him travel easily between golf tournaments, strike business deals and keep charity and personal-appearance commitments.

Always mindful of the need to be safe, a quality imbued in him by Krinock from the outset, Palmer employed a series of experienced pilots during his aviation career, the most recent being Pete Luster, who was his chief pilot for 20 years.

“Safety is the name of the game, and I have learned more by flying with Pete than anyone could imagine,” said Palmer.

Longtime friend Russ Meyer, Cessna’s chairman emeritus and the man who arranged all of Palmer’s aircraft acquisitions, saw Palmer’s commitment to safety firsthand. “When Arnold got into the left seat, he was a professional pilot in every respect. He started going to FlightSafety in 1977, and he earned his type rating in every one of the Citations he owned.”

For 40 years, Palmer also was a member of the Cessna jet family, providing input to new designs, from the Citation III to the Citation X, added Meyer. “Arnie helped us host engineering briefings. He was there because he was an aviation professional who could speak knowledgably to other pilots, and he was treated as a peer by chief pilots of many major companies.”

EXPERIENCING THE BREADTH OF AVIATION

Besides operating business airplanes, Palmer had the privilege of flying a variety of commercial and military aircraft. He piloted commercial transports, from the Boeing 747 to the McDonnell Douglas DC-10, and he flew with the U.S. Navy’s Blue Angels and U.S. Air Force’s Thunderbirds flight demonstration teams.

In May 1976, Palmer and two other pilots set a round-the-world speed record by taking off from Denver’s Stapleton International Airport in a Learjet 36 and heading east, circling the globe in under 58 hours. The record flight included brief refueling stops in Boston, Wales, Paris, Tehran, Sri Lanka, Jakarta, Manila, Wake Island and Honolulu.

The second leg of the flight was supposed to be from Boston to Paris, but Palmer and his crew were forced to land in Wales because of 35-knot headwinds. They encountered ice on the way from Tehran to Sri Lanka and were unable to use the airplane’s DME, so they followed the coastline of India to get safely to the destination.

Many of Palmer’s most enjoyable aviation experiences were in the cockpit of his Citation X. Shortly after he took delivery of the first production model of the fast business jet in August 1996, he flew it non-stop from Latrobe to Scotland in what would be a memorable trip to the birthplace of golf, St. Andrews.

And it was in the Citation X in January 2011 that Palmer made his last flight as pilot in command on a trip from Palm Springs, CA, to Orlando.

Pete Luster recalls that trip well. “I was not aware that word had gotten out that this was his last flight, but halfway across Texas, the controllers started talking about it. They always like chatting with us. At the end of the conversation, they said we were cleared direct to Orlando. That was pretty unusual, but that clearance, plus a nice tailwind, enabled us to made good time. We flew the 2,100 nautical miles in three hours and 17 minutes.”

In his later years, Palmer continued to travel in the Citation X – he just sat in the back instead of up front.

In accepting NBAA’s Meritorious Service to Aviation Award in 2010, Palmer summed up his lifelong love affair with aviation well: “As a young boy I dreamed of flying, and aviation has allowed me to visit places all over the world and spend extra time with my family.

“I met a lot of great people while playing golf,” continued Palmer, “but business aviation has a lot of great people, too. It’s been a wonderful trip.”

Learn more about Arnold Palmer’s amazing life and career in his two autobiographies: “A Golfer’s Life,” published in 1999, and “A Life Well Played: My Stories,” released by St. Martin’s Press on Oct. 11.

Access the digital edition in the mobile app to hear excerpts from NBAA’s interview with Arnold Palmer and to view more photos from Palmer’s storied career.

HONORED TO BE HONORED Arnold Palmer was the only sports person to receive both of the U.S. government’s highest honors – the Presidential Medal of Freedom, which he won in 2004, and the Congressional Gold Medal, which was bestowed in 2009. He also was a member of several halls of fame, including the World Golf, American Golf and PGA halls. In addition, he was named “Athlete of the Decade” for the 1960s by the Associated Press. His aviation awards are equally impressive. His hometown honored him in 1999 by renaming the local airfield Arnold Palmer Regional Airport. He served on the Westmoreland County Airport Authority board for many years, and was recently reappointed chairman prior to his passing. In 2010, Palmer received NBAA’s Meritorious Service Award, the association’s highest honor, given to an individual who, by virtue of a lifetime of personal dedication, has made significant, identifiable contributions that have materially advanced aviation interests. In the same year, he won the FAA’s most prestigious award for aviators, the Wright Brothers Master Pilot Award, for having exhibited professionalism, skill and aviation expertise for at least 50 years. He was inducted into the Cessna Jet Pilots Association’s Hall of Honor in 2014. When asked by NBAA about how he views the aviation awards he has won, Palmer said, “I was flattered anytime I was told that I did things right in aviation. I am very honored to be honored, and I am happy I was able to encourage people to get into aviation.” |

| FROM CESSNA TO CESSNA

Arnold Palmer learned to fly in single-engine Cessnas, and in later days, he used a Citation X to support his businesses. In between, he owned numerous other business airplanes, many of which have had the famous tail number “N1AP.” |

|

| Aircraft Model | Purchased |

| Aero Commander | 1962 |

| Aero Commander 560F | 1964 |

| Jet Commander (lease) | 1966 |

| Lear 24D (lease) | 1968 |

| Citation I | 1976 |

| Citation II | 1978 |

| Two Citation IIIs | 1981, 1985 |

| Citation VII | 1992 |

| Two Citation Xs | 1996, 2006 |

Throughout his career, Arnold Palmer was involved in numerous charitable activities. As a long-time member of the board of directors of Latrobe Area Hospital, he held six major fundraising golf events for the hospital. Also, for 20 years, he served as the honorary national chairman of the March of Dimes Birth Defects Foundation.

But perhaps the initiative that was dearest to him was his role in the effort to dramatically improve the health, development and well-being of children. “Of all of Arnold’s many charitable initiatives, the No. 1, by far, is the Arnie’s Army Charitable Foundation, which primarily supports the Arnold Palmer Medical Center in Orlando,” said lifelong friend Russ Meyer, Cessna’s chairman emeritus. “That facility comprises the Arnold Palmer Hospital for Children and the Winnie Palmer Hospital for Women & Babies.”

When Palmer and his wife Winnie toured the small neonatal intensive care unit and pediatrics wing of Orlando Regional Medical Center in the mid-1980s, they resolved to expand the facility and help make it a full-fledged women and children’s hospital that would eventually become one of the world’s best. By lending his name to the facility and helping raise the necessary funding, Palmer realized that goal.

International Business Aviation Council Ltd.

International Business Aviation Council Ltd.