July 1, 2019

Aviation stakeholders are working to ensure that manned aircraft and drones can safely coexist.

The presence of unmanned aircraft systems (UAS) in the National Airspace System (NAS) continues to increase, with the proliferation of recreational, first responder, commercial and other applications. As UAS use increases, so does the importance of safe integration of UAS into an air traffic management system originally designed for manned aircraft.

A number of notable incidents highlight the need to mitigate the risk of conflicts between manned and unmanned aircraft, especially near airports.

- In February 2018, a UAS overflew a Frontier Airlines aircraft on final approach to Nevada’s McCarran International Airport, violating a prohibition on UAS operations within five miles of an airport without notifying ATC and the airport (for recreational operations) or authorization (for Part 107 commercial operations).

- Hundreds of flights at Gatwick Airport near London, England, were cancelled over a two-day period in December 2018 following reports of UAS sightings close to the airfield. Law enforcement officials believe the interference was intentional but not an act of terrorism.

- Just a few days later, London’s Heathrow Airport experienced a similar incident, although normal airport operations were only disrupted for about an hour. Within days of the incident, a man was arrested.

- In January 2019, two UASs were spotted over New Jersey’s Teterboro Airport, 17 miles away from Newark Liberty Airport. The UASs were reported to be operating at about 3,500 feet. The FAA responded with traffic management initiatives, including a ground stop and then a ground delay program at Newark. Operations at Teterboro were not impacted.

“These incidents emphasize the fact that safety is a shared responsibility, requiring due diligence from both manned and unmanned aircraft operators,” said Heidi Williams, NBAA’s director of air traffic services and infrastructure. “We can take extreme measures and segregate airspace, but that doesn’t get us to true integration.”

“Business aviation is a vital economic contributor, and unmanned commercial aviation is now part of that realm,” said Brad Hayden, president and CEO of Robotic Skies and chair of NBAA’s UAS Working Group. “But we also have to recognize that UAS operators are often new entrants to the aviation industry and have their own unique operational requirements. We need to include them in the discussion.”

LOW-ALTITUDE AUTHORIZATION AND GEOFENCING

So, how does the aviation industry as a whole – manned aircraft pilots, UAS operators, airports and air traffic managers – mitigate the risk of UAS incursions into controlled airspace while complying with the current regulatory framework?

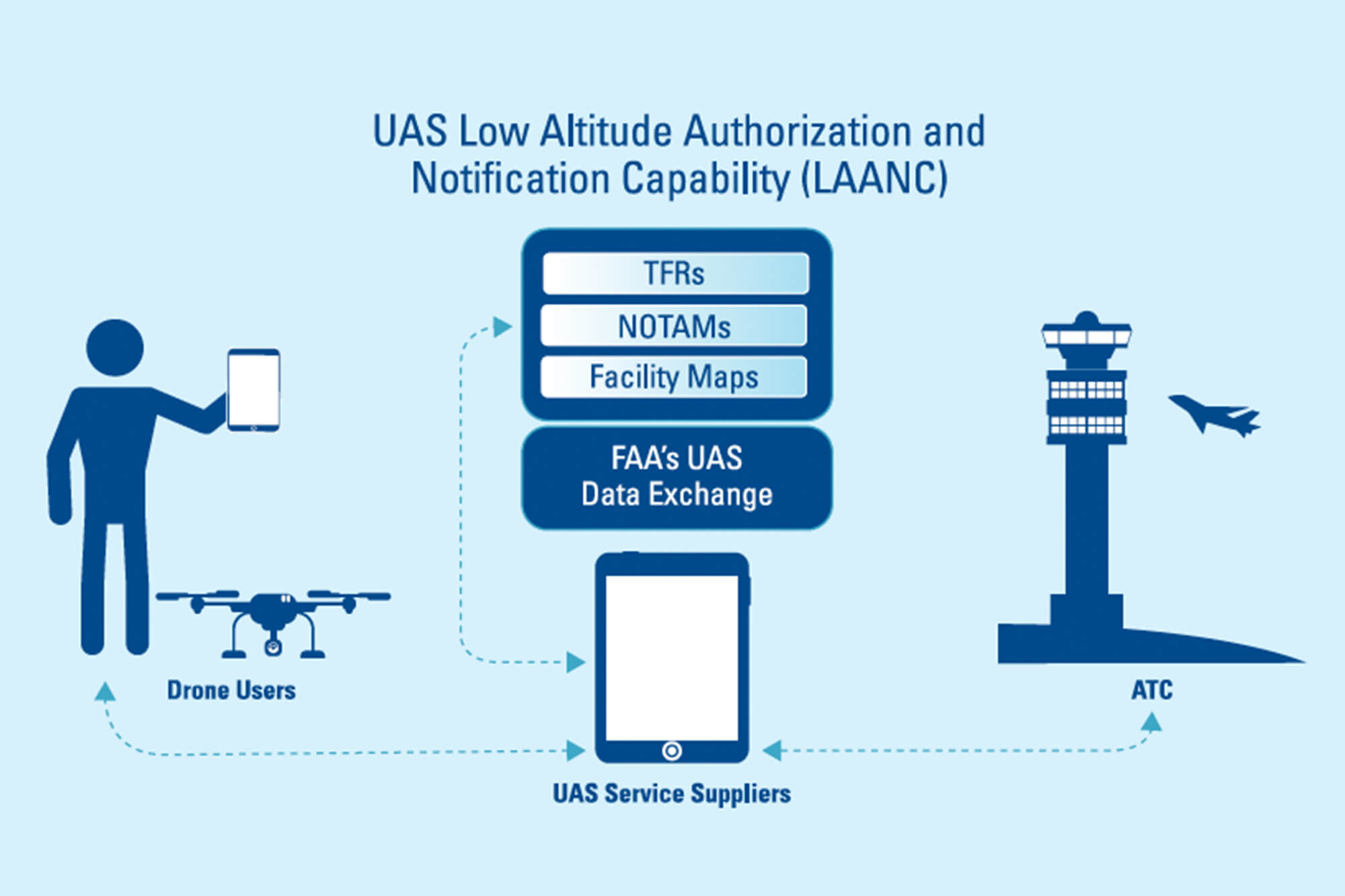

One method of managing the safe integration of UAS in controlled airspace, particularly near airports, is the Low Altitude Authorization and Notification Capability (LAANC), a collaboration between the FAA and industry that has been aggressively implemented and now is deployed at nearly 300 air traffic facilities covering approximately 500 airports.

In the U.S., commercial UAS operations under FAR Part 107 are authorized to operate in Class G airspace below 400 feet. Operations in con-trolled airspace require FAA approval, which can be requested via LAANC. The protocol is used to process, in near real-time, airspace authorizations below approved altitudes in controlled airspace. Requests to operate at other altitudes are for-warded to the ATC authority responsible for that airspace (typically the control tower) for review.

UAS operators also receive TFRs, NOTAMs and facility maps when requesting authorization through LAANC.

Geofencing is another way to mitigate the risks associated with UAS incursions.

Geofencing uses GPS to create virtual geo-graphic boundaries. For example, some UAS models will not operate if the GPS coordinates indicate the aircraft is in restricted airspace. Geofencing is built into different airframes, with no set standard or requirements, so the geofencing capabilities of a UAS depends

on the individual manufacturer.

Aside from the lack of standardized guidelines, geofencing can severely limit the capabilities of a UAS for legitimate uses. First responders and commercial operators may have a legitimate need to fly in restricted areas, for example. Currently, some UASs used by first responders have to be returned to the manufacturer to have geofencing features disabled.

“Geofencing may be appropriate for hobby drones, but commercial and public-use operators need to have the flexibility to fly where needed, as long as they follow the applicable regulations and procedures,” said Hayden.

EDUCATION AND CONTINGENCY PLANNING

Jason Schwartz – airside operations planner and designated UAS point person for the Port of Portland, which owns and operates Oregon’s Portland International Airport, as well as general aviation facilities Hillsboro Airport and Troutdale Airport – emphasizes the need for education for all stakeholders. The Port of Portland uses its own website, social media and a pilot hotline to provide UAS- related information to manned aircraft pilots and UAS operators.

The Port of Portland’s pilot information hotline describes current rules for commercial and recreational UAS operations within five miles of an airport, along with phone numbers for appropriate control towers so UAS operators may request authorization to operate closer to an airport. The Port of Portland also participates in industry briefings and panels at events around the region and works closely with Oregon’s Department of Aviation.

“The majority of UAS operations are not very close to airports, nor do they interfere with airport operations,” said Schwartz. “It’s important to acknowledge that only a very small percentage of [UAS] incidents are impacting airport operations, and only a subset of those are intentional, so the key is providing adequate information for those who intend to operate legally and safely. Education and collaboration are our two biggest tools.”

Nevertheless, the incidents described above underscore the importance of contingency planning, especially in the event of intentional or nefarious interference with airport operations, which Schwartz explained is a separate issue from inadvertent incursions, adding that the Gatwick incident demonstrated the need to have plans to deal with this type of event.

Schwartz emphasizes that airports should develop collaborative response plans in conjunction with local authorities. He suggests that airports work with local law enforcement, ATC and other parties to develop these plans, which should include:

- How authorities should be notified

- What the communications should be between responding parties and ATC

- How continuity or suspension of flight operations will be handled during an event

MAXIMIZING UAS POTENTIAL

UAS represent a major advancement in aviation technology, and new-generation VTOL and autonomous aircraft are coming in the next several years. Successfully integrating all these innovative, capable aircraft fully into the national airspace is crucial for the future growth of the aviation industry as a whole.

“Safe integration of commercial unmanned systems into the National Airspace System is critical,” declared Hayden. “Our challenge is to achieve that integration without unnecessarily stifling innovation. It’s a delicate balance.”

CURRENT REGULATIONS LIMIT

TECHNOLOGY SOLUTIONS

Some have suggested simply using technology to disable or interrupt communications between an operator and a UAS in unauthorized airspace as a way to mitigate the risks posed by an unintentional UAS incursion or the intentional activities of a rogue UAS. However, current laws and regulations create challenges to that approach.

The current regulatory framework limits what airports can do in response to a UAS that poses an airspace hazard, explained Jason Schwartz, airside operations planner and designated UAS point person for Oregon’s Port of Portland.

For example, the FAA prohibits interference with an air-craft in flight, which is considered a form of air piracy. In addition, Federal Communications Commission rules may apply to the communications between the pilot and an aircraft, so interrupting those communications constitutes a violation of FCC regulations.

International Business Aviation Council Ltd.

International Business Aviation Council Ltd.