Despite the business aviation industry’s longstanding efforts to stem loss of control inflight (LOC-I) accidents and prevent aircraft upsets, such accidents show no sign of waning, even as training providers have added LOC-I prevention and recovery courses.

Why is that? The chief training officer (CTO) for a major training provider believes the answer lies in hands-on understanding of the forces behind an aircraft upset and going beyond simple rote instruction on upset prevention and recovery training (UPRT) techniques.

“The key to it all is the quality of the instructor, which is problematic when the vast majority of instructors out there have never taken an airplane past 60 degrees of bank,” the CTO explained. “The first rule of UPRT after recognizing the problem is to manage the angle of attack and get control authority back. In theory, I can teach that to anyone; the problem lies in the instructor’s ability to thoroughly describe the situation so the student understands and can apply those techniques.”

“I often ask in class, when is the last time you heard the word ‘aerodynamics?’” said Mike Romeo, FlightSafety International’s director of advanced training programs for Dassault and Pilatus aircraft. “Most pilots have to think back 20-30 years to their primary flight training, yet we’re using it every time we fly.”

However, even in the case of aerodynamics taught during primary flight instruction, what is covered is the aerodynamics of the normal flight envelope. Certain aspects of aerodynamics can change significantly in the upset domain.

Such lack of awareness of basic principles of flight also points to what NBAA Safety Committee member Jeff Wofford, CAM, and chief pilot and director of aviation for CommScope, termed “a 1960s mindset” when it comes to training. “We spend a lot of time training to respond to engine fires that don’t occur that often, but typically only cover aerodynamics at the very beginning of flight training,” he said. “We need to find a way to keep that at the forefront.”

Wofford has firsthand experience of that need, as several years ago he was in the right seat of a Lear 31A that experienced an upset event caused by wake turbulence from a heavy commercial airliner.

“We rolled well past 90 degrees of bank,” Wofford recalled. “Fortunately, the junior pilot in the left seat had just finished upset recovery training two weeks before, and he recovered the aircraft successfully.

“Our chairman was in the back of airplane at the time,” Wofford added. “That experience convinced him that our operation absolutely needed to require UPRT.”

Numbers Don’t Lie

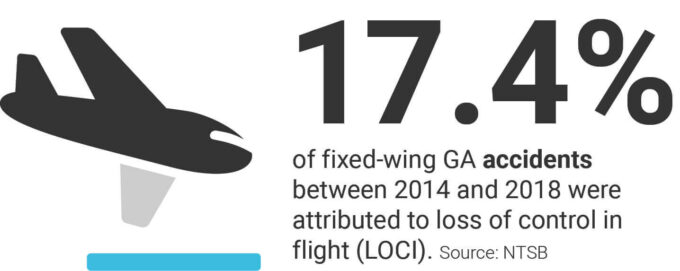

One may also look at recent accident reports to understand why such training is necessary. Although LOC-I represents just 17.4 percent of all GA aircraft accidents, the NTSB says LOC-I contributes to more than 46 percent of all fatalities. Data also indicates that LOC-I is the primary cause of fatal accidents in business aircraft, and the second-leading cause of total accidents.

Following the crash of a regional airliner in 2009, the FAA mandated simulator-based training for all Part 121 operators. However, no mandate exists for UPRT training for Part 91 and 135, placing the onus on training providers to offer UPRT options beyond the scope of existing regulations. Business aircraft pilots must then find the time and resources necessary to undergo this extra training, in addition to their initial and recurrent requirements.

FlightSafety International first offered a simulator-based UPRT course for Gulfstream G550 crews six years ago. Today, its one-day UPRT course may be tailored to many other specific aircraft and avionics packages and may be added to recurrent training or be conducted as a standalone program.

Louis Poth, FlightSafety’s advanced training director for Gulfstream and Bombardier aircraft, explained how the UPRT course is structured.

“It comprises a four-hour ground school to review the academics of aerodynamics, stability and control, turn performance and G loading, and recovery procedures, followed by applying those techniques in the simulator for recovering from extreme attitudes, full aerodynamic stalls and upsets. It boils down to recognition and prevention, and if unable to avoid, recovery.”

“Technology is great,” Romeo added, “but at the end of the day, when those things aren’t doing what you want them to do, you need to remember you can still grab the controls, point the nose where you want it, and fly the airplane.”

That can be a stressful experience for business aircraft pilots trained to prioritize the comfort of their passengers.

“We all strive for smoothness in normal operations, but that [mindset] must be abandoned in upset recovery,” Romeo said. “It’s not an end-all, be-all, but it hopefully ingrains in their minds they can maneuver the aircraft around.”

“The regulations teach us to fly on autopilot 90 percent of the time, and even in the simulator, we train crews to click on the autopilot at 1,000 feet,” added the CTO. “We fly like we train, yet we still sit back and ask why we’re still having manual aircraft control problems. Well… duh!”

“Technology is great, but at the end of the day, when those things aren’t doing what you want them to do, you need to remember you can still grab the controls, point the nose where you want it, and fly the airplane. ”

Mike Romeo Director of Advanced Training Programs for Dassault and Pilatus Aircraft, FlightSafety International

Poth also noted the risk in misunderstanding how fly-by-wire (FBW) systems function to keep the aircraft within the safe operating envelope.

“I think referring to ‘normal control law’ does a disservice to pilots, as it implies that you can’t stall the airplane,” said Poth. “FBW was designed to prevent that, but not to fix it. It won’t know how to get out of it if the system malfunctions or has other issues.”

If any aircraft, FBW or conventionally controlled, leaves the normal envelope, the pilot becomes the last line of defense.

Two Different Approaches

The question of whether to take simulator-based or in-aircraft UPRT training is a common one, with each offering unique advantages and disadvantages.

Simulators offer the ability for pilots to train in scenarios that can’t be safely replicated in an actual aircraft, such as upset recoveries at low altitude. They can also be adapted to a variety of different business aircraft types, providing more accurate control feel and sight pictures than what can be experienced during in-aircraft training that is usually conducted in light, single piston or turbine-powered aerobatic aircraft.

What is commonly misunderstood is that the fundamental concepts of UPRT are based on underlying aerodynamic and physical principles. Unlike many other aspects of flight training, the basis of UPRT is not type-specific.

“Simulators can be good at replicating post-stall activity, when your ailerons work in reverse in a deep stall,” said the CTO. “First and foremost, it’s about using all available control inputs to return the blue side up and brown side down; the procedures and recovery are the same [regardless of being in an aircraft or a simulator.]”

Conversely, simulators can’t fully replicate an actual upset, whereas in-aircraft training enables pilots to experience those sensations in real-time.

“I believe it’s important to experience UPRT in an actual aircraft to feel the kinesthetic effects, G-forces, sensory overload and startle factor,” Wofford declared. “A simulator can come close to all that, but it won’t be quite the same.”

The ICAO Manual on Aeroplane Upset Prevention and Recovery Training – developed over five years with expertise from 40-plus organizations, including OEMs – states that an integrated (live and app/web-based, in-aircraft, simulator (non-type-specific), and simulator (type specific) solution is the most effective and should be integrated into the career path of all commercial pilots.

Concerns about LOC-I remain so vexing that even competing training providers generally acknowledge the strengths and weaknesses of each approach. Some have even partnered with other providers to offer both options in accordance with the ICAO standard, calling the two types of UPRT “complementary.”

“In-aircraft UPRT can make you a more competent and confident pilot,” acknowledged the CTO, whose company is known primarily for simulator-based training. “We often teach through fear of the consequences of non-compliance. Recovering an aircraft following an upset teaches through accomplishment and understanding.”

While not every pilot will have access to both types of UPRT training, trainers and pilots agree that aviators need to have practical, hands-on awareness, prevention and recovery training by qualified instructors to recognize and avoid LOC-I.

“UPRT isn’t flying aerobatics,” Wofford concluded. “Whether the training is on-wing or simulator-based, it’s critical to know how to prevent and get the aircraft out of a condition in which it’s not flying properly.”

Regardless of the form of training used, one thing is certain: If pilots do not change the way they train to mitigate LOC-I, the accident rate will remain high.

Review NBAA’s loss of control inflight resources at nbaa.org/loci.

International Business Aviation Council Ltd.

International Business Aviation Council Ltd.