A next generation of quieter supersonic airplanes would halve the time to fly between major international destinations, but new standards still need to be developed.

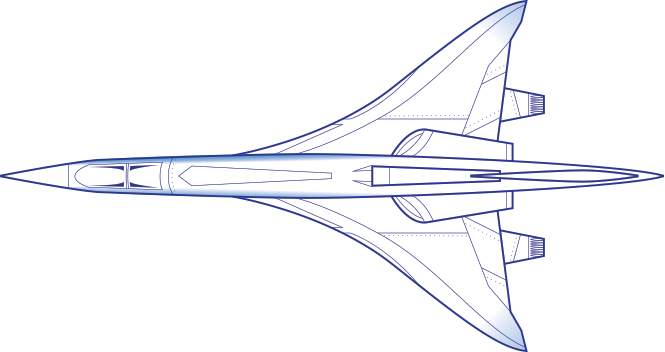

The word “supersonic” evokes images of Chuck Yeager, Top Gun fighter jet flybys and the iconic Concorde airliner. However, the word could soon be synonymous with a series of new, time-saving, transoceanic business aircraft.

A number of supersonic aircraft are on the drawing boards, including five in the United States, one in Japan and another in Russia. If manufacturers’ projected timetables hold true, operators may be whisking passengers across the oceans at speeds from Mach 1.2 to 2.2 within five to seven years.

To get there, the contenders not only need to design for speed and comfort, but they must address multiple technical challenges – fuel efficiency, CO2 emissions, noise levels on takeoff and landing – plus the ultimate dilemma: sonic booms.

“Speed is something you can never have enough of,” said Preston Henne, who retired from Gulfstream Aerospace in 2013 as senior vice president of programs, engineering and test programs. “The challenge is going supersonic. There are a lot of tough barriers. I don’t think anybody has the right solution yet. But there is enough interest and enough people willing to spend some money to try to develop a supersonic business jet. Someone is going to do it. And they are going to do it sooner rather than later. I think it’s going to happen, and the reason is because the market is there.”

The primary advantage of a supersonic business aircraft would be halving the time to fly between major international destinations, such as New York-London, making it feasible for same-day transoceanic roundtrips.

So, it’s no wonder that development of supersonic business jets continues apace.

- In October 2017 Boston-based Spike Aerospace

flew an unmanned SX-1.2 subscale demonstrator

of its S-512 supersonic design to validate stability and control. - Boom Supersonic’s one-third-scale, two-crew XB-1 “Baby Boom” demonstrator, which is being developed outside Denver, is scheduled to fly by the end of this year.

- Reno, NV-based Aerion Corp., which has worked with Airbus, General Electric and more recently Lockheed Martin, plans to proceed directly to a full-size pre-production AS2 aircraft.

All three programs are targeting flight testing and initial production aircraft deliveries in the 2021-2025 timeframe. In addition, they are promising high-tech cabin interiors, befitting an aircraft with a purchase price of between $100 million and $200 million. For example, Spike is planning a windowless cabin with the interior walls acting like a display screen, projecting business data for discussions, entertainment or live video of the view outside the aircraft.

Other projects are not as far along. Supersonic Aerospace International, led by J. Michael Paulson – son of Gulfstream founder Allen Paulson, who proposed a supersonic business jet back in the late 1980s – worked with Lockheed Martin’s legendary Skunk Works design team on a “quiet supersonic” design, but went on hiatus after the 2008 economic downturn. Now, Paulson is again seeking potential investors or OEM participation in a larger follow-on QSST-X design.

The Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency’s “system integration of silent supersonic airplane technologies” research project is exploring designs for lighter airframes and low drag following low-sonic-boom experiments featuring a 7.9-meter aircraft flying at Mach 1.39.

Russia’s Aerohydrodynamic Research Institute showed a wind-tunnel-tested scale model of a supersonic commercial aircraft at the MAKS International Aerospace Salon in Moscow in July 2017.

Gulfstream has been involved in supersonic-related research for some time. “Gulfstream maintains a small team committed to researching sonic-boom mitigation and technologies needed to enable civil supersonic flight capability,” said Dan Nale, Gulfstream’s senior vice president of programs, engineering and test.

Even if these aircraft projects achieve their ambitious delivery schedules, they may not be allowed to overfly the United States because of an FAA ban on flights exceeding Mach 1, which was implemented in 1973, shortly before the British-French Concorde began flying to the U.S. Indeed, they may not even be able to use American coastal airports because there are no current landing and takeoff (LTO) noise standards for supersonic aircraft.

To certify a new aircraft type, “you obviously need to know the standards that you have to comply with,” explained Ted Ellett, a former FAA chief counsel. Now a partner in the Washington, D.C. office of the global legal firm of Hogan Lovells, Ellett is advising Aerion regarding the effort to have the supersonic ban modified to an acceptable noise standard.

“The regulations that currently exist in Part 36 of the FAA’s rules for subsonic aircraft unfortunately are silent with respect to landing and takeoff noise requirements for supersonic aircraft,” Ellett said. “The kinds of things that make sense for subsonic aircraft just don’t make sense from a supersonic perspective. The physics are different. The types of engines are very different.”

“Compared to a subsonic aircraft, a supersonic aircraft will have significant excess thrust and a significantly faster minimum drag speed on takeoff,” said Mike Hinderberger, Aerion’s senior vice president for aircraft development. “Standard takeoffs may have noise-abatement features, such as automatic thrust reduction, accelerating climbs and automated flap scheduling. Approaches will be less different [than those of subsonic aircraft], though the aircraft would prefer steeper than three-degree glideslopes where allowed.”

According to the FAA, the agency has been “actively engaged with manufacturers and regulatory entities worldwide as the interest in civil supersonic flight has increased. The FAA continues to assess the requirements for allowing domestic supersonic flight.”

The FAA is collaborating with the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) Committee on Aviation Environmental Protection (CAEP), particularly its noise and emissions technical working groups. The CAEP’s Supersonic Task Group was initiated in 2004 and expects to issue by 2025 recommended standards for LTO noise and LTO emissions, Mach cut-off (flight conditions in which sonic booms do not reach the ground’s surface) and “low boom.”

The standards adopted by ICAO, the FAA and other aviation authorities around the world “should consider the interdependencies among noise, emissions and fuel burn,” suggested Ellett. “You can create a very stringent noise standard to require the aircraft to be very quiet for landing and takeoff, but the impact of that, when the aircraft operates at cruise, would be that the aircraft would burn a lot more fuel and create more emissions.” He said the standards need to be “economically reasonable and technologically practicable and take into account the differences between a supersonic aircraft and a subsonic aircraft.”

Ellett added: “We’re optimistic that the standards that are going to be developed are going to be practicable. If they’re not, the technology will be workable, but the projects will not be economically viable.”

An Aerospace Industries Association supersonic working group is advocating for a balanced approach. The group – which includes representatives from Lockheed Martin, Raytheon, United Technologies, General Electric, Rolls-Royce, Honeywell, Embraer, Gulfstream, Aerion and Boom – is also lobbying Congress to encourage the FAA to work with industry to facilitate acceptance of civil supersonic aircraft.

“The real question that needs to be answered is how quiet is quiet enough?” said Gulfstream’s Nale.

The heavy, fuel-inefficient, high-thrust Concorde produced a nominal boom of 105 perceived level of decibels (PLdB), the relative loudness as perceived by the human ear. Paulson said SAI’s patented “virtually boom-less” supersonic aircraft design “is well over 100 times quieter” than the Concorde. NASA’s planned Low Boom Flight Demonstrator experimental airplane is targeting about 75 PLdB or lower; the planned first flight for the Lockheed Martin X-plane is 2021, with “community-response flight testing” expected to take place between 2023 and 2025.

Nale said, “We are talking about radically different noise levels than experienced from the Concorde or a typical fighter aircraft, more akin to a very low and distant rumble of thunder, or hearing your neighbor close the trunk of their car.”

Aerion is touting its “boomless cruise” Mach cut-off concept for flights over the U.S. “Our primary case is there is no sonic boom reaching the ground at speeds approaching Mach 1.2,” said Hinderberger. “What is still being researched is the sensitivity – how much margin is needed to ensure the boom doesn’t reach the ground, given the uncertainty of atmospheric measurements.”

Honeywell and Rockwell Collins have been working with NASA on sonic boom calculation algorithms, factoring in temperature and wind speed, together with cockpit displays to assist pilots in flight planning and controlling the “boom carpet width and forward throw,” the main considerations when approaching a coastline at supersonic speed.

Gulfstream’s Nale believes flying a supersonic business jet will be “very similar” to flying a subsonic jet. “Modern flight controls and fly-by-wire systems do an excellent job of compensating for the aerodynamic effects of transonic and supersonic flight. The transition from subsonic to supersonic flight in modern jets is almost imperceptible, but it can sometimes be noticed as a very slight bump as the aircraft transitions into a completely supersonic flow field.”

“Where supersonic pilots are most likely to feel the effects of speed is on their displays,” Nale added. “Distances will shrink at a surprising rate, airborne traffic will be quickly overtaken, and pilots will have to carefully plan their arrivals and descents to effectively transition from high and fast to the terminal environment.”

So, although the technical details and regulatory parameters for a new generation of supersonic civil aircraft remain to be worked out, it appears increasingly likely that a Mach 1 or faster business jet is just over the horizon.

VIEW THIS ARTICLE IN THE APP

This article originally appeared in the July/August 2018 issue of Business Aviation Insider. Download the magazine app for iOS and Android tablets and smartphones.

International Business Aviation Council Ltd.

International Business Aviation Council Ltd.