Routes

Routes are used to ensure that flights stay with the “flow” of traffic, remain clear of special use airspace, avoid congested airspace, and areas of known weather where aircraft are deviating or refusing to fly.

Route information is published in various sources for different purposes, different users and different time frames. The most current information is located in FAA advisories and in the NOTAMs. These sources document changes to standard routes for the current date or for a special event.

Reroutes

There are many instances when ATC needs to move air traffic away from, or into, a particular area of airspace. When this happens, traffic managers will implement reroutes – a common route, or set of routes, that are designed to move aircraft off of their originally planned routes and onto something else. Reroutes may be issued due to weather, excess volume, active military airspace, or other reasons.

Normally, air traffic controllers will clear a flight via the route specified by traffic management. The flight may be rerouted in the air or on the ground. The operator should file or amend flight plans with the appropriate routes when the aircraft is 45 minutes or more from the proposed departure time. If within 45 minutes from departure or airborne, ATC facilities will enter the reroutes.

In accordance with Federal Air Regulations (FAR), all operators have the right of refusal of a specific reroute and may elect an alternative. Alternatives include but are not limited to ground delay, diversion to another airport or a request to stay on filed route.

If a reroute cannot be accepted due to safety of flight or fuel concerns, the pilot is required to notify the controller that the route cannot be accepted for safety reasons. The controller will work with the pilot to find an acceptable route. If it is known beforehand that the route cannot be accepted, the pilot should notify the clearance delivery controller. However, there may be no alternatives and the flight could be required to accept a delay on the ground until the route becomes available.

Routes and reroutes can be issued as either required, recommended, or “FYI”. Required reroutes, as the name implies, are required to be used by all aircraft captured in the scope of the reroute. Recommended reroutes are those which ATC would LIKE operators to use, but are optional. Finally, FYI reroutes are issued by ATC to let operators know that they are available if the operators wish to utilize them.

Current reroute information can be found online by visiting the FAA’s Current Reroutes web page or the Advisories Database.

Types of Routes

Routes come in several different varieties including:

- Preferred Routes (sometimes called “pref routes”)

- Playbook Routes

- Coded Departure Routes (CDRs)

Preferred Routes

Preferred routes are the normal, everyday routes that ATC would like operators to file. These routes were developed to increase system efficiency and capacity by having balanced traffic flows among high-density airports, as well as de-conflicting traffic flows where possible. Preferred routes are those that operators will most commonly file.

Preferred routes can be found online in the FAA’s Route Management Tool.

Playbook Routes

Playbook routes are a set of standard routes that ATC can utilize to fit a particular set of circumstances, when the preferred routes are not available. These routes were created to allow for rapid implementation as needed.

Playbook routes are available online in the FAA’s National Playbook. Within the Playbook, there are 5 different types of routes:

- Airport-specific routes – designed to manage traffic to or from specific airports

- Airway Closure routes – designed to be used when a primary airway is closed (typically due to severe weather)

- East to West Transcon routes – designed to manage traffic from the eastern US (primarily the northeast) to the western US

- Regional Routes – designed to be used for traffic between specific regions of the US

- West to East Transcon routes – designed to manage traffic from the western US to the eastern US (particularly the northeast)

For more detailed information about Playbook routes and how they are used, visit NBAA’s National Playbook page.

Coded Departure Routes (CDRs)

Coded Departure Routes are a combination of coded air traffic routings and refined coordination procedures, designed to reduce the amount of information that needs to be exchanged between ATC and flight crews.

CDRs are typically used at high capacity airports and during inclement weather to make communication between ATC and flight crews more efficient. They are designed for aircraft and crews that have been properly equipped and trained to use them, allowing flight crews and ATC to quickly and clearly communicate entire routes using only eight characters to describe that route.

For example, for a flight between Teterboro, NJ (TEB) and Naples, FL (APF), the route might be: KTEB DIXIE V276 PREPI OWENZ LINND AZEZU L453 PAEPR M201 BAHAA AR21 CRANS LLNCH KAPF. Normally, this route would have to be read by ATC and read back by the crew. The use of a CDR allows this route string to be condensed to “TEBAPFAZ”, dramatically reducing the amount of data to be communicated.

Like the preferred routes, CDRs can be located online in the FAA’s Route Management Tool.

How to Read Routes

Reading routes from the National Playbook, an FAA advisory, or the Route Management Tool is not at all difficult, but can be confusing to those who have not seen them before.

Routes are normally divided up into origin segments and destination segments (unless the route is a very simple one, issued between only two specific airports) and accompanied by guidance on what flights are affected and when to use the routes.

Reading Reroutes from an Advisory

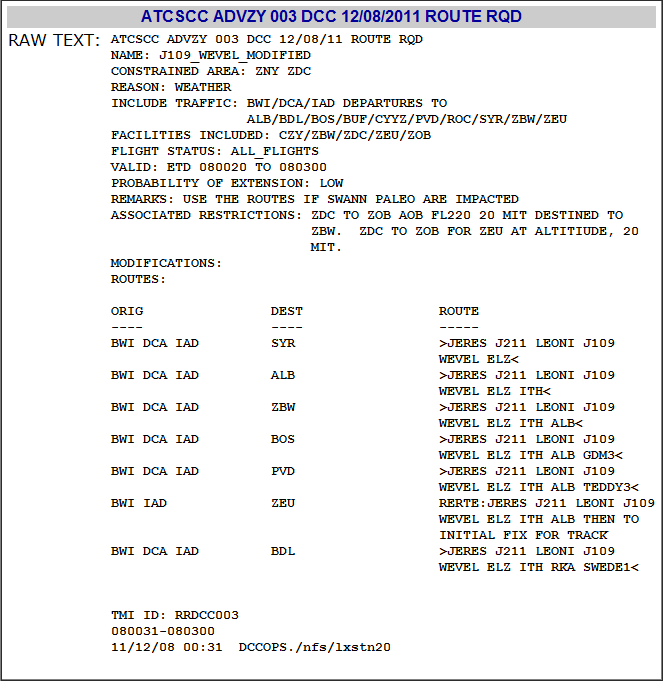

For example, the screenshot below is a reroute issued in an FAA advisory, affecting flights between the DC metros airports and NY State and New England.

First, note at the very top of the Advisory the words “ROUTE REQ.” This means that this is a required set of reroutes.

Next, in the middle of the Advisory, there is a chart showing “ORIG” (origin), “DEST” (destination), and ROUTE. So, if a flight is leaving from IAD and flying to BOS, the appropriate route would be “JERES J211 LEONI J109 WEVEL ELZ ITH ALB GDM3”

Please note the remarks located above the chart, indicating when the route is valid, when to use the routes, and what miles-in-trail (MIT) restrictions can be expected.

Reading Reroutes from the National Playbook

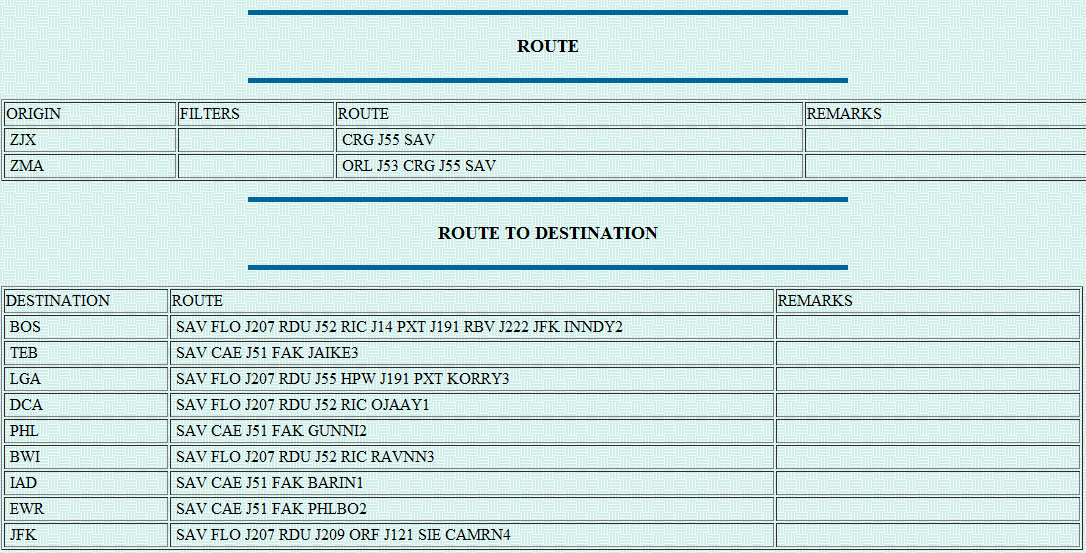

Reading reroutes from the National Playbook can be a bit different, but still not difficult. The screenshot below shows a flight from Fort Lauderdale (FLL) to Teterboro, NJ (TEB).

In this format, the table is broken into two sections and the route is broken into two parts. Our example flight is leaving from FLL, which is contained within Miami Center (ZMA). So, using the “ORIGIN” section of the table, the first part of the route string would be “ORL J53 CRG J55 SAV” (note that the string stops at SAV). Now, jump down to the “DESTINATION” section and pick the route up at SAV – “SAV CAE J51 FAK JAIKE3.”

Severe Weather Avoidance Plan (SWAP)

A specific application of reroutes is known as the Severe Weather Avoidance Plan (SWAP), which is a formalized program that is developed for areas susceptible to disruption in air traffic flows, caused by thunderstorms. Each air traffic facility may develop its own strategy for managing the severe weather event. Their plan then becomes part of the overall daily operations plan.

Since each weather event is unique, the response is tailored to meet the specific forecasted and actual events of the day. The SWAP plan is issued through the Planning Telcon, which the Air Traffic Control System Command Center (ATCSCC) conducts every 2 hours. The results of that telcon are published as an advisory, available to all users, after the telcon is complete. Additionally, routes issued in support of SWAP are issued as route advisories by the ATCSCC. They may be found on the FAA Current Reroutes or Advisories Database web pages.

The best way to respond to SWAP, once it has been implemented, is to be informed about conditions in the NAS and plan appropriately. Be prepared to respond to rapidly changing weather conditions which may require new routes, often longer, to be issued. ATC may request flights to evaluate flight conditions after the weather has passed. If a flight is capable, it is encouraged that they volunteer their services.

The question is often asked, “Why do I get delayed on the ground when the weather is VFR?”. The answer is that there may be times when the weather enroute or at your destination airport is what prevents the departure, rather than the weather at the departure airport. If aircraft are all deviating through a small opening in the weather, traffic flow becomes very condensed and complex, thereby requiring additional traffic management initiatives.

On the other hand, if the destination airport has a reduced airport arrival rate (AAR) for some reason, a flight may be delayed because of TMIs or compliance with a GDP.

The best advice is to pay attention to what is being said on the radio and be informed.

International Business Aviation Council Ltd.

International Business Aviation Council Ltd.